The War on Glamour

What is the purpose of fashion in hard times?

I just spent a whole series talking about war and all the clothing associated with it. But what about the clothing back at home? Military expert Joshua Kerner said, in the series, that military clothing tends to get more ornate in peace time and more simple in war. But does that hold in the civilian world?

Sort of. But it’s not that simple. Fashion historian Liv Elniski tells us why.

Skirt lengths supposedly rise when the economy buckles. This theory, referred to as the “hemline index,” suggests a direct relationship between women’s wardrobes and economic conditions. Although skirts did shorten briefly during WWI ( referred to as “war crinolines” by the fashion press, who promoted the fabric- saving style as patriotic and practical), this “hemline index” hypothesis is a little too seductive in its simplicity. While fashion is, and has always been, a reflection of its time, truly there’s not any predictable way that clothes respond to hardship.

In a 2017 essay, The Looks of Austerity: Fashions for Hard Times, author David Gilbert remarks that “the relationship between austerity and the austere is complicated, and any temptation to look for neat correlations obscures the multiplicity of responses.” A person’s wardrobe is not just a mirror of economic circumstance, but a tangible record of adaptation, ingenuity, and coping. Let me tell you what I mean1.

As a student in New York City who works part-time, nearly all of my money goes towards rent and sheer survival. Whatever remains gets funneled into my personal upkeep and aspirations of glamour.

In the oppressive heat of this last New York summer, I met a sixty-something-year-old vintage seller on the outskirts of Central Park East to purchase feathers: a huge bundle of antique ostrich plumes, along with a molting black boa that is now draped, like a decadent relic, around a mirror in my room2. Feathers are just part of my latest affliction.

Over the last year, I have become the kind of person who rouges her lips each day with the same deep plum lipstick (aptly named Film Noir), and who, every two weeks, has their Louise-Brooks-inspired bob trimmed to geometric perfection (I’d be nothing without my hairdresser, Kaitlyn). Somewhere along the way, I also developed a consuming obsession with millinery.

I know where this is all coming from: I’ve become preoccupied with the clothes and accessories of 1920s and 30s films. Recently, I’ve been spending more time in the art house movie theaters that show these films, because there is absolutely nothing like watching Greta Garbo or Kay Francis projected to larger-than-life proportions, suspended in a softly lit frame, dripping in bias-cut silk, and crowned by a perfectly fitted cloche.

Between the late 1910s and 1940, Hollywood produced some of the most tantalizing on-screen fashions in modern history. Extravagant gowns by leading costumers provided a phantasmagoric world-building experience with thousands of shimmering beads and eleven-yard sable borders (like the one that trimmed the opera coat by Gilbert Adrian for Garbo in her 1937 film Camille).

Though these preposterously glamorous screen vixens seem to share little with my life as a student in New York, their highly manufactured visages were always intended to inspire ordinary people. For instance, in her 2017 essay, Signs of Wear: Encountering Memory in the Worn Materiality of a Museum Fashion Collection, design scholar Bethan Bide reflects on how her grandmother constantly evoked early Hollywood cinema in everyday conversation: noting that the woman who read the six o’clock weather reminded her of Joan Crawford, or declaring that the cut of her new jeans were “very Jane Wyman.”

For women like Bide’s grandmother, Hollywood starlets provided a template for dressing and living fashionably—and for imagining an alternative glamorous life. While few regular people could afford the clothes worn on screen, they could certainly emulate their effect through hair, posture, and makeup. As Bide writes, her grandmother’s fascination with silver screen style “enabled her to transform the post-war London landscape into a glamorous place …through the way she wore a new belt or the positioning of a hair clip.”3 It’s little gestures that make all the difference.

Although Bide’s grandmother’s life in 1940s post-war London and my comfortable life in Brooklyn are worlds apart, in our own contexts, we are engaged in a similar ritual of daily world-building. Both of us use style, gesture, and self-presentation—to inhabit a world that feels otherwise lost to time and circumstance. We both believe that it’s still possible to embody the idiosyncratic glamour of Marlene Dietrich or Joan Crawford—so long as we are prepared to really commit to reapplying lipstick every hour or so4.

In the process of transforming my apartment into a makeshift 1930s-style boudoir—and my comically small Brooklyn closet into a miniature archive of screen-fashion eccentricity—I’ve begun to realize that fashionable glamour is just as much about moxie and intention as it is access5. As I see it, knowing the right keywords to type into the eBay search bar matters more than material wealth or the resources of a studio costume designer. My own glamour hinges on search terms and second-hand luck, but that old Hollywood’s glamour hinged on something even more precarious: supply chains.

With the onset of World War II, studio designers were suddenly robbed of the luxurious materials needed to create movie costumes. Hitler’s annexation of Czechoslovakia cut off the supply of bugle beads, once indispensable to Gilbert Adrian’s dazzling on-screen evening gowns. The lamés, brocades, silks, and velvets that once adorned Claudette Colbert as the Egyptian queen in Cleopatra (1934) became scarce. The remaining stock of lace trim, beads, jewels, and sequins were hoarded—jealously guarded by designers who found themselves bartering among one another for these now-rare commodities. And just like that, the chiffon-and-sequin-lined portal to cinematic glamour dissolved. Never again would a movie budget tolerate a long, decadent sable border. The more austere costume designs of WWII signalled the fading out of Hollywood’s most glittering era.

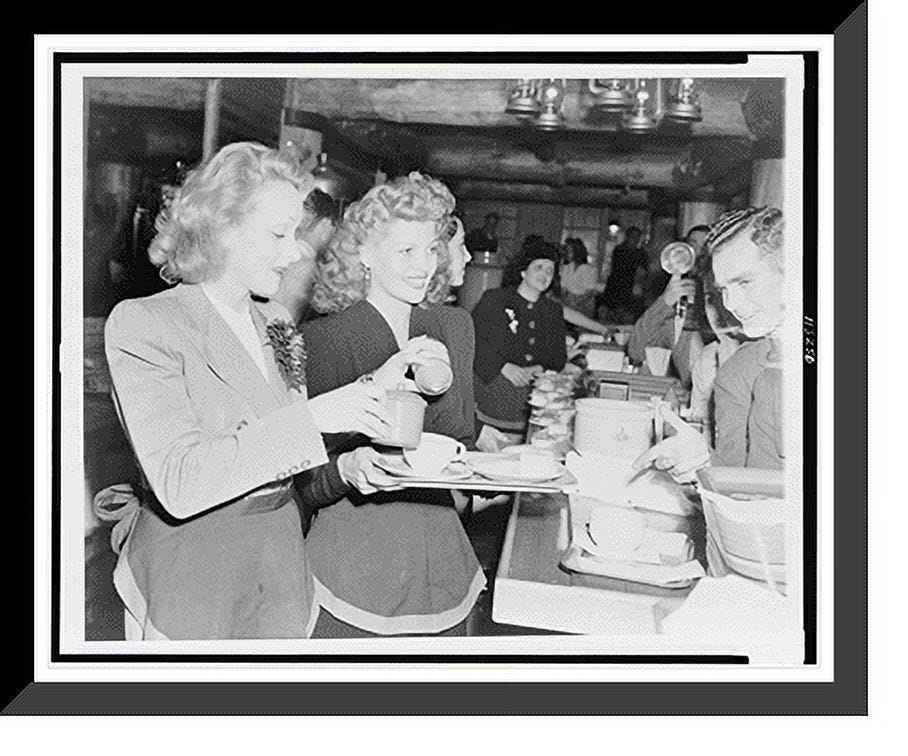

Stars like Ginger Rogers, who had spent the 1930s doused in endless spools of tulle, chiffon, and feathers, pared down their on-screen wardrobe. Even madcap Carole Lombard appeared in off-the-rack clothes in the 1940 film They Knew What They Wanted.6 Marlene Dietrich traded her sultry, erotic veils and slithering black dresses for military-inspired tailored suits , as she entertained troops on hastily-erected plank stages in the jungles of the Pacific. The biggest on-screen-divas packed their bags, tied their hair in a scarf (Rosie-the-Riveter-style), and went off to sell war bonds across the country.

By 1942, all reserve stocks of beads, jewels, and sequins had been depleted, and studio workrooms were functioning under make-do-and-mend conditions. Tailored wool ensembles came to define the austere, pared-down look of 1940s film. Laura (1944), starring Gene Tierney and costumed by American fashion designer Bonnie Cashin, exemplified this new austerity: streamlined silhouettes stood in for the opulence that previously dazzled on-screen divas and their devotees.

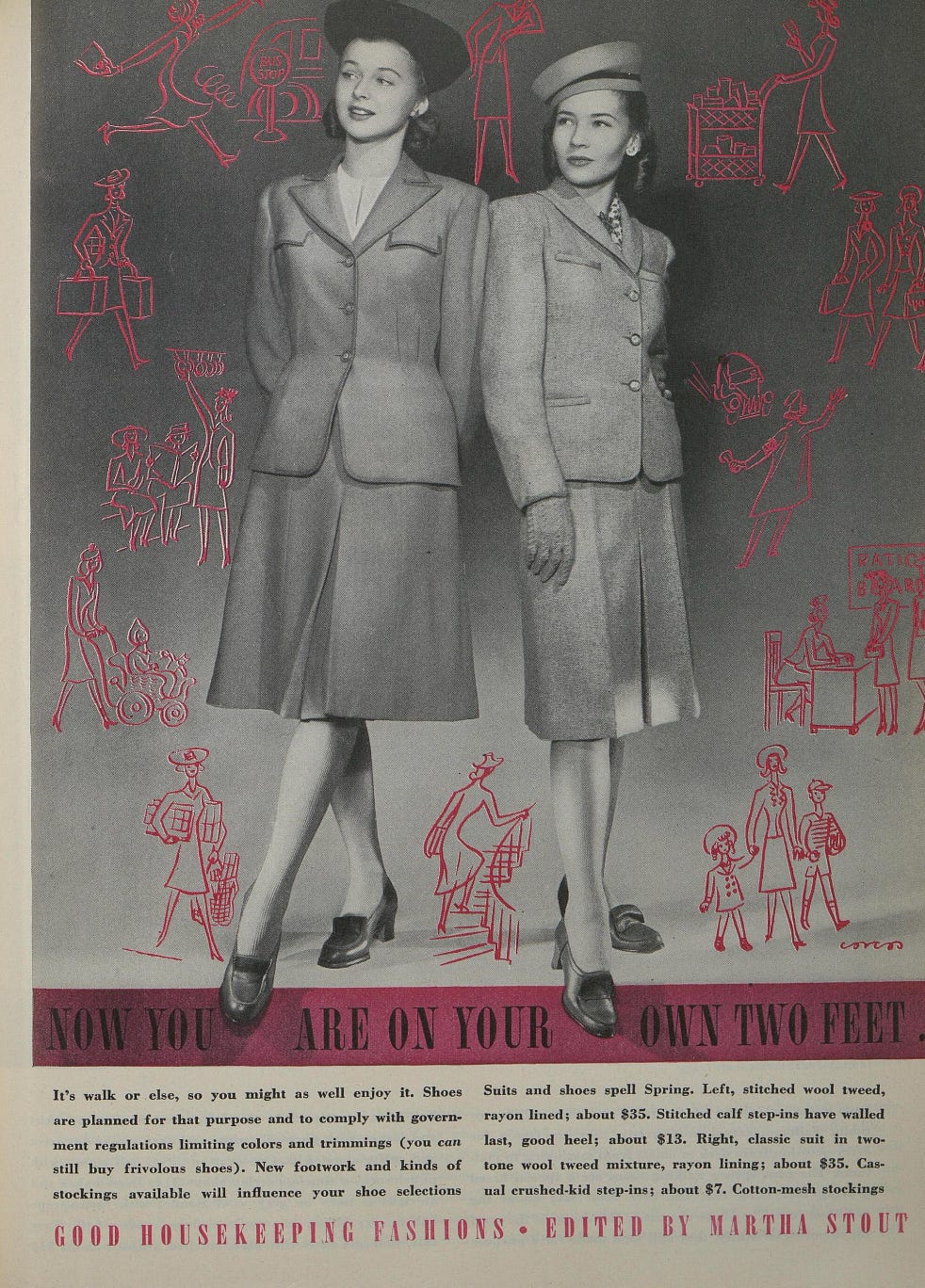

Everyday women’s fashions in mid-century America faced a similar fate. Almost immediately after the United States entered WWII, shoe-making materials were diverted for military production, and civilian footwear was rationed. The U.S. government allowed citizens to purchase only three new pairs of shoes a year. The occasional exception was made only if you could prove that the new shoes were not being purchased to simply follow fashion or maintain personal appearance7.

Quickly, the footwear industry pioneered designs made from unrationed materials such as cloth, rope, and wood. These constraints resulted in fabulously dramatic platforms and bold architectural forms. In this way, shoes of the 40s feel more theatrical than those of other periods: they prove that even in moments of frugality, fashion finds a way to imagine new possibilities for beauty.

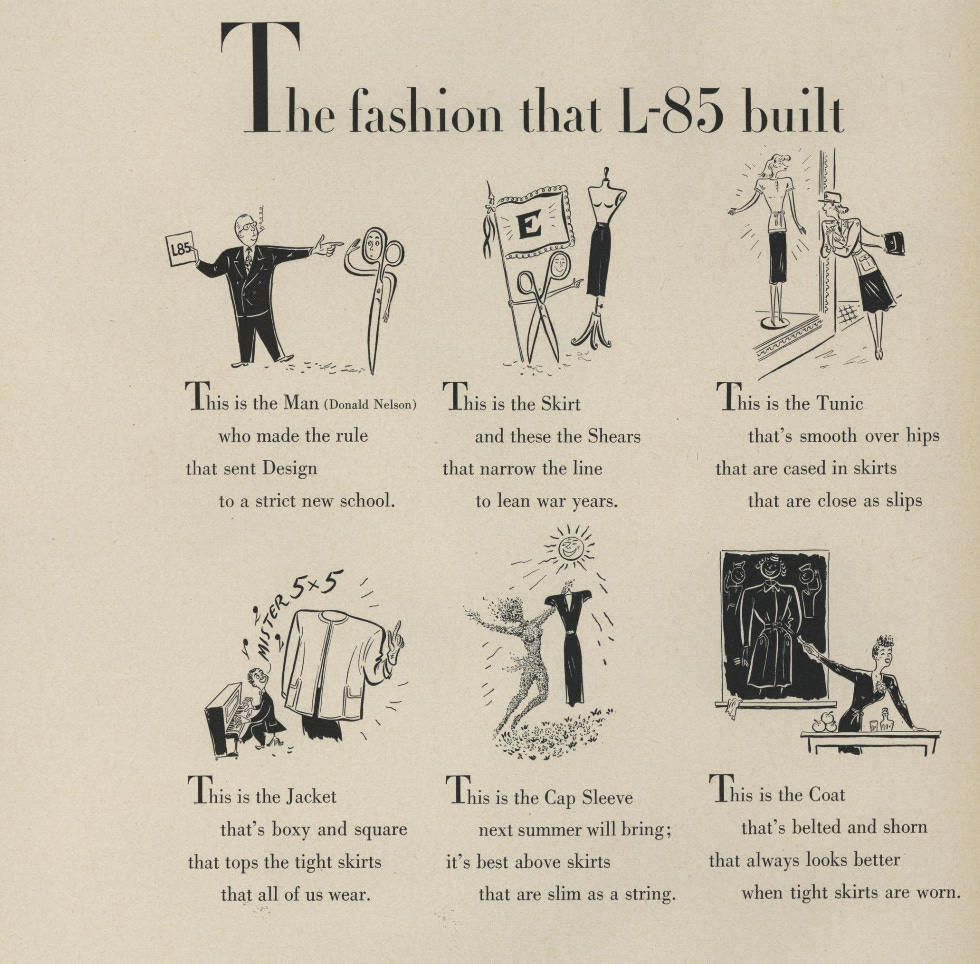

Rumors swirled that, similarly to shoes, clothing would soon be rationed as well. Just like the costume designers had, consumers rushed to local stores to buy up all the dresses and blouses they could, before the stock of clothing was depleted. These anxieties were well-founded: on April 10, 1942, the United States government initiated General Limitation Order L-85, which rationed “Feminine Apparel for Outer Wear and Certain Other Garments.”

L-85 restricted the use of wool, silk, rayon, cotton, and linen, and the order placed particular emphasis on garment measurements and lengths. Skirts couldn’t be too long or full, to conserve precious textile resources. French cuffs, double-layered fabric, leg-of-mutton sleeves, pleating, shirring, and inside pockets were all banned from women’s clothing. The resulting look was simplified, straight dresses and skirt suits, free of lapels or heavy ornamentation. But even in the era of L-85, fashion wasn’t so simple.

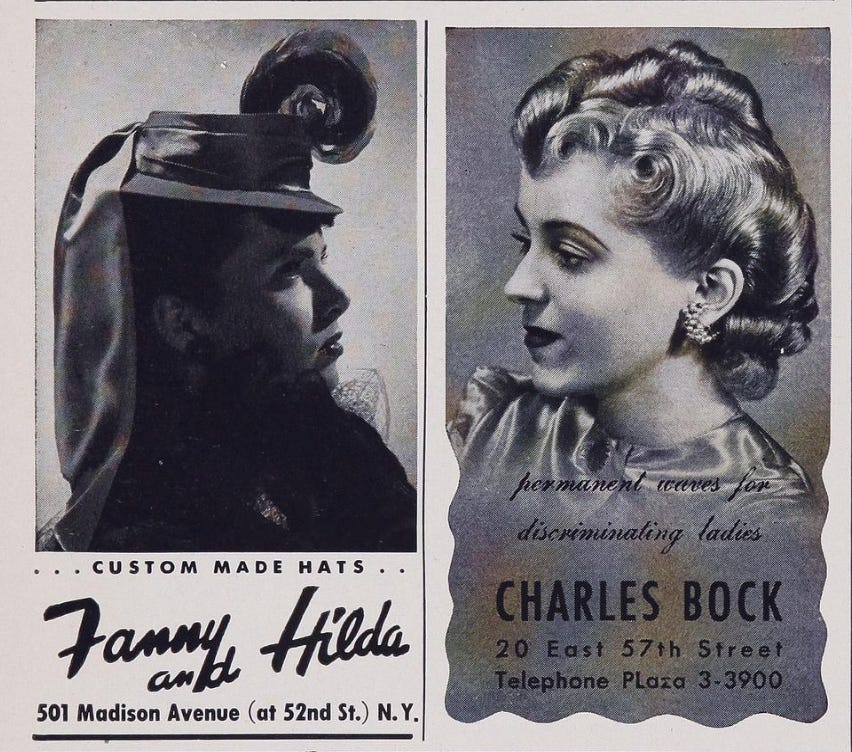

L-85 aimed to stall any radical changes in women’s styles. In effect, it sought to freeze fashion in 1942—putting the kibosh on new seasonal purchases. But, of course, stylish women persisted. Even amid these limitations, they sought creativity elsewhere, most notably in their hair: ladies lovingly curled their locks into “victory rolls,” topping their patriotic coifs with whimsical, decorative millinery—something, fortunately, untouched by rationing. Milliners like Lilly Daché pioneered turban styles, wide, flat brims, and towering architectural forms embellished with felt and straw flowers, bird feathers, and bejeweled brooches.

Claire McCardell, who had emerged as a major player in American design, pioneered wrap dresses, separates, and ballet flats among other items that complied with wartime restrictions. One of her most widely celebrated creations, the “Monastic dress” was an entirely pleated shift, paired with a simple string belt, that allowed the wearer to shape the garment to her own body. McCardell’s clothes were meant to adapt to you, rather than demanding your body conform to the dictates of a garment. Designers like McCardell began establishing a new modern design vocabulary of ease, flexibility and frugality in America. And then, almost as suddenly as it had emerged, this wartime practicality and simplicity was cast aside.

The year 1947 has an almost mythical status in the fashion history canon. The style stagnation that came from L-85 was abruptly interrupted by French designer Christian Dior’s “New Look,” or what he called the “Bar Suit.” This wasp-waisted hourglass shape was less about innovation than it was about the explosive reintroduction of glamorous excess and ostentatious abundance. The Bar Suit’s heavy circle skirt required approximately twenty yards of wool and its sharply sculpted, nipped-in bodice marked a dramatic return to pre-war fashions.

The New Look reintroduced clothing that acted as a conduit for aspiration, desire, and spectacle. It emphasized excess and sculptural artifice (and inevitably, discomfort and constraint) as peak femininity. However, many women, including designers like Claire McCardell, extended their simple, sporty, paired-down wartime looks into peacetime—believing that modernity could, and should, be expressed through democratic ease.

While it’s tempting to pit McCardell and Dior against one another (backward-looking, restrictive European fashion vs. forward-looking “American look”), their work is more productive when viewed as two different (and valid) responses to a moment in history. Both the otherworldly glamour and the practical simplicity can be viewed as emancipatory. Sequins and feathers and furs can be just as vital to everyday life as raw practicality.

Feeling glamorous allows me to live in a world of my own fantasies. A world that feels, if not perfect, at least okay. And, for myself, glamour currently provides a momentary escape from the specter of impending authoritarianism in the United States and the scourge of athleisure that has taken over every street corner of New York City.

At the tail end of last winter, a dear family friend named Briget mailed me a 1950s mink fur coat. Briget is a true estate-sale, church-basement-thrift-store warrior—she managed to find this coat for $30. Fortunately for me, it was not her size. Upon the first day below 50 degrees in New York this fall, I freed my mink from the confines of a dust bag.

Even though my mink jacket is fraying at the edges and doesn’t necessarily scream “untouchable leading lady,” it still makes me (momentarily) feel like Rita Hayworth. Add the right lipstick and a fresh haircut, and you’re armed. Bide’s grandmother knew this. The classic Hollywood screen sirens knew this. Glamour, in its most honest expression, is a performance that provides an escape, pieced together out of aspiration, desire, and whatever the materials and garments the moment affords. It can help us fashion our realities—to soften the rough edges and uncertainties of a particular moment in time and space.

The Looks of Austerity: Fashions for Hard Times (2017) by David Gilbert, Via Fashion Theory Journal

(Everyone needs a reliable feather dealer!)

Signs of Wear:Encountering Memory in the Worn Materiality of a Museum Fashion Collection (2017) by Bethan Bide, Via Fashion Theory Journal

Or to spend your evenings on eBay searching for a 1980s-does-40s wool-gabardine skirt suit (pro tip: search low-to-high price)

For more on this, check out Moxie: The Daring Women of Classic Hollywood (2024) by Raissa Bretana and Ira Resnick

Clothing Goes to War: Creativity Inspired by Scarcity in World War II (2022) by Nan Turner

My mother (who was glamorous and committed to lipstick) also used to say things such as, ‘very Veronica Lake’ when referring to a one-eyed hair do. It would seem that the studios/actors intentionally developed a signature style -as the writer is also doing. The archaic meaning of glamour is magic and illusion.

There is a wonderful, strange little art museum on the Columbia River in Washington state that hosts a permanent exhibit of "Théâtre de la Mode" mannequins from the 1945 Paris haute couture season. Because of the Nazi occupation of Paris, the clothes for this season were only made at a tiny scale, on wire dolls.

https://www.maryhillmuseum.org/inside/exhibitions/permanent-exhibitions/theatre-de-la-mode

These tiny dresses prove that "new look" was already being dreamed up in the midst of WWII, before anyone knew who would win, or if prosperity would ever return.

It's an amazing exhibition and I highly recommend it for anyone willing to drive 2 hours outside of Portland, Oregon! The museum itself is in the middle of nowhere with beautiful views, and feels like an art deco mirage.