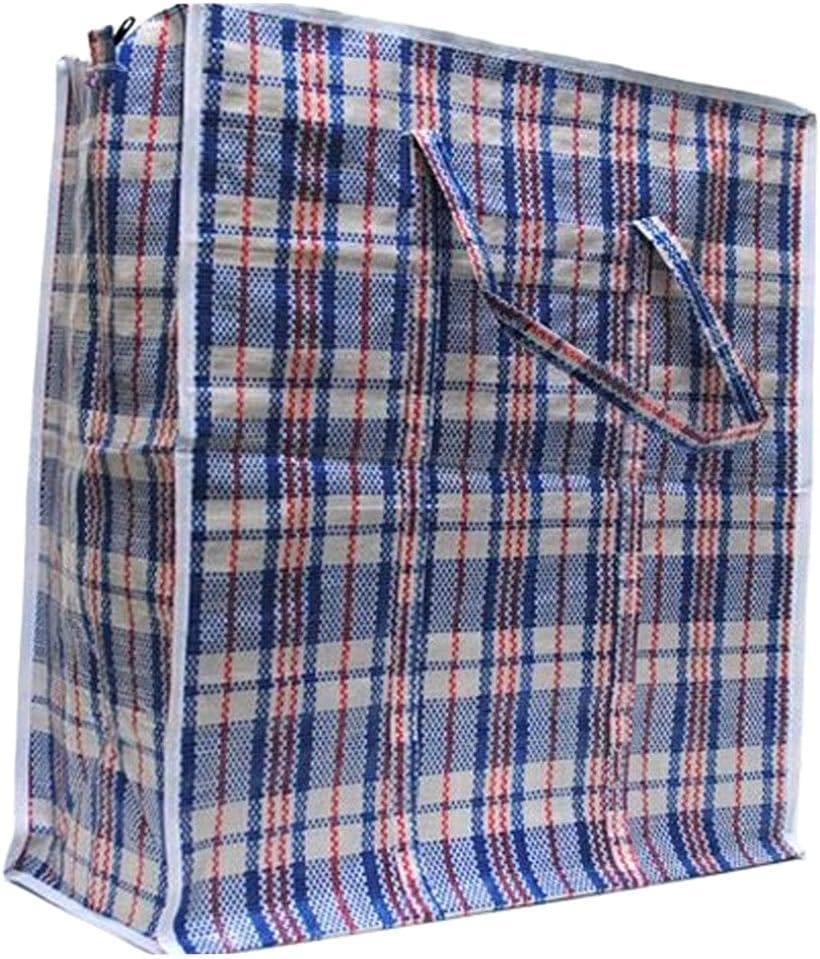

Ghana Must Go

A bag with baggage

I got an email from a mental health social worker in Ireland. Sarah, this social worker, told me that patients often come into hospital in crisis, with only the clothes on their backs. Upon leaving the hospital, they often end up putting all their belongings in a trash bag. Trash bags are very functional and efficient, but, as Sarah said, they “are not a good expression of care and something I aim to change.”

Sarah is in the process of setting up a program to give discharged patients a proper bag to transport their belongings. So when Sarah started to research sturdy, affordable bag options, she was recommended a particular type of plastic sack bag. You’ve definitely seen it around.

And perhaps its name will make you feel as uncomfortable as it made Sarah feel.

It’s called a "Ghana go Home bag" or a "Ghana must go bag.”

But the name comes from Nigeria.

“The bags had always been popular: they were big and spacious and sturdy enough for long-haul travel,” Shola Lawal writes in this story of the bag. The bags used to be nameless in Nigeria, until January 17, 1983, when the bags “were wanted in Lagos markets with an intensity never experienced before.”

Shehu Shagari, the first democratically elected Nigerian president, declared that all undocumented migrants living in the country needed to leave. Immediately. Over two million people, with no papers, were told to leave in two weeks, or else face jail time.

“If they don’t leave, they should be arrested and tried and sent back to their homes,” President Shagari said. “Illegal immigrants, under normal circumstances, should not be given any notice whatsoever.”

Half of these two million immigrants had come from Ghana.

Many of these Ghanaian immigrants had come to work in Nigeria during their oil boom. In 1974, Nigeria’s oil wells were spitting out some 2.3 million barrels a day and the Nigerian economy was on the ups. Meanwhile, Ghana was facing a tremendous recession, combined with famine and political insurgency. So when Nigerian recruiters came to Ghana looking for oil workers, they didn’t have to do much convincing. Ghanaians gladly made the move.

However, when Nigeria’s oil market crashed in 1982, their national rhetoric turned xenophobic. As Lawal writes, politicians “blamed African migrants, especially Ghanaians, for the flailing economy. Ghanaians had taken all the jobs and brought crime to Nigeria and, if elected, they would chase them out, they promised.” It’s also possible, according to writer Omotola Saba, that this expulsion could have been a retaliation: back in 1969, around 140,000 Nigerians had been abruptly forced to leave Ghana. And so now the shoe was on the other foot.

Diana Olaleye, in an article for The Book Banque, wrote that “Nigerian police physically harmed immigrants – beating and gassing them, in the hope that they would depart immediately.”

With a lack of resources and support, without a home, without a car, Ghanaian immigrants had to turn to something that could tide them over: these spacious, sturdy bags. The bags became replacements for a car, a home, for resources. Families packed these bags full of everything they owned, making the bags weighty with both personal effects and political symbolism.

Today, the Ghana Must Go bag is everywhere in Nigeria. “You see people in the streets carrying the bag, in the buses, traveling,” says Olaleye. “We had quite a few housemaids or helpers in the house when I was growing up and the Ghana Must Go bag was one of the bags they’d use to move into the house. It was pretty normal.” Although most people, Olaleye admits, “don’t really understand the implications of this bag or why it’s called Ghana Must Go.” This history was not taught in schools.

Oddly enough, this is the bag’s story in many countries, even outside of Nigeria. In Kenya they are known as Nigeria bags, and Zimbabweans call them Botswana bags. They seem to always be the bag of The Other: the carryall of the immigrant who is forced to pack up everything and leave.

Sarah, the social worker in Ireland, was horrified by all of this. “That was definitely NOT the message we want to send with our duffelbag programme!!!” she wrote me. She searched around for another big, sturdy bag that could accompany people out of the hospital. But simply couldn’t find one. She has looked into plasticized paper bags, bags made out of fishing line, or trying to get used bag donated. But she’s finding it hard. Truly, pragmatically speaking, there’s no bag that can do what the Ghana Go Home can.

But have heart, Sarah.

It turns out the GGH bag contains multitudes. There is in fact one place that doesn’t want to name the bag for another nationality. One part of the world that proudly takes ownership of the bag. And it’s not in Africa.

It’s Hong Kong.

In Hong Kong, these bags are so popular that the "official" Hong Kong tartan is based on them.

“Every person in Hong Kong knows this bag,” says secondary school teacher Jacky Ming, who registered the tartan (yes, anyone can register an official tartan ). “The price is very low and it is very useful. It has a square pattern – like tartan.” Ming calls this tartan “Passion of Hong Kong.”

So why does Hong Kong, at least according to Mr. Ming, get to lay claim to the bags? Well, it’s at least somewhat closer, geographically, to where the bags actually come from. Which is not Africa.

The bags come from Japan.

They plastic material was invented to be strong and waterproof, which made it useful as a construction sheet. This is how the material is primarily used today in Japan, according to Christopher DeWolf. The Japanese version is blue. No checker pattern there:

DeWolf writes:

Shortly after its invention, the fabric traveled to Taiwan, where local manufacturers applied the familiar red-white-blue pattern. After it was imported to Hong Kong it quickly became ubiquitous, wrapped around bamboo scaffolding and strung over hawker stalls to shelter them from the rain.

Sometime in the 1970s, a fabric merchant in Sham Shui Po named Lee Wah used the fabric to make a bag in his Yen Chow Street shop, Wah Ngai Canvas. (That shop is now closed, but other nearby shops still sell the original fabric.) It turned out to be a massive hit and the bags soon became a must-have for Hong Kong households. They were especially useful for transporting goods across the border to mainland China when immigrant families returned home to see their relatives.

This is of course the same durability that made the bags a matter of life and death to millions of Ghanaian migrants.

And it’s also the same versatility that has appealed to fashion designers over the years.

When Hong Kong-based artist Stanley Wong traveled to London in 1989, he was shocked to see the bag on display at an upscale boutique. “It slapped me in the face. I woke up. I thought, ‘Outsiders, foreigners think we have interesting things, but we don’t care. We just take it for granted.’”

Wong went on to create rwb300 a company which makes bags and wallets that riff on the bag pattern, and sale proceeds support the New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association.

And Wong is not the only artist who has taken back the narrative of the bag…

New York-based photographer Obinna Obioma teamed up with artist Chioma Obiegbu and fashion stylist Wuraola Oladapo to create images that Obioma describes as a fusion of both western and African designs. This series is called Anyi N'Aga, Igbo for “We Are Going.”

Johannesburg-based brand Wanda Lephoto makes garments that also toy with the pattern of the bag. They put it beautifully:

“It is always interesting to observe what, where and how Africans move. Often having to reappropriate our own culture against the commercial viability the West has over us, we seldom look past aestheticism to unwrap the true nature of who we are.”

Wanda Lephoto calls the garments in this line “Me fie” which means Trust me. The pattern is a tribute to the trust, the leap of faith that was placed in the bags.

And so. What to do with all of this?

This could just be me. But I think it’s important not to erase the history in this bag. Not to try to deny the story (or the name) of the Ghana Must Go bag, but rather to acknowledge the design, and the role it played in a painful history. This is a terrible story of how a simple accessory was made to fill the gaps- to take the place of housing, of government policy, and of aid programs. It was ultimately a poor substitute. But it performed its one small task heroically. And has received its due.

So, dear Sarah, I do think it is ok to use these bags. With the acknowledgement and respect for what they are, and the job they are always asked to perform.

But if you really don’t want to call it “Ghana Must Go,” I don’t blame you. There are other names for the bags. Fashion writer Omotola Saba tells me it can also be called a “Ghanaian sack. ”And in Ghana, according to Christopher Agyemang, the bag has a name in the Akan language, since Ghanaians don’t want to ridicule themselves or remind themselves of the past. It goes by ‘efiewura suame’ meaning Landlord, help me carry my bag.

Pronunciation guide by Ogochukwu Okoli.

Thank you Sarah Mclaughlin, for writing in with your question, and thank you to fashion writer Omotola Saba for the Nigerian perspective, and thank you to Hong Kong-based listener Billy Potts for the Hong Kong context! And thank you, dear reader, for reading.

Other Articles of Interest

Nicole Lipman's harrowing article on SHEIN and fast fashion for N+1

"SHEIN’s predicted $60 billion annual revenue is the equivalent of selling seven black sweetheart neck long sleeve shirts to all 7.8 billion people on Earth."

Another two podcast episodes coming soon, before I tap out and focus solely on this book that I’m writing. I can’t wait to tell you about it.

I loved this piece as an African! I knew this history so it’s amazing to see it shared with a larger audience.

Also the NY-based luxury brand Bode's store bags are definitely inspired by these (probably the versions seen in NYC's Chinatown). And Sandy Liang did her take in a pattern for her collab with Baggu.