Here you go, chapter 2.

+ the transcript!

Our story starts in Japan. Because if you look at images of Japan from the late 1880s, all little upper-class boys are dressed exactly the same.

You’ll notice that everyone in these woodblock prints is dressed in a western style, but the boys specifically are wearing something called a gakuran. It’s a school uniform (and sometimes you still see boys wearing gakuran around Japan today).

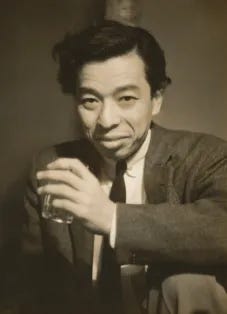

I can’t summarize the whole podcast here, but the gakuran is going to be really important for explaining Ivy style’s relevance today. Because this drab dark uniform is what a young man named Kensuke Ishizu grew up wearing.

Ishizu is going to be the hero of our story. He is going to eventually change the whole way Japan dresses, which will then impact the way the whole world dresses. And next chapter, there’s going to be a meet-cute when Ishizu goes to visit Princeton University. Because Princeton is the birthplace of Ivy league style.

Princeton, sometimes called “the best Southern school in the North” in the 1920s and 30s, had this unusual cocktail of assets that gave rise to a new kind of casual clothing. The largest factor is that Princeton’s student population is extremely sporty, and students would wear their sport clothes right from class to dinner.

The key thing about the fashion at Princeton is that the clothes had just… softened. They weren’t padded and constructed out. The shoulders of the jackets were soft and natural. The shoes were meant to be slip ons. Ties were meant to be loose and not constricting.

But- you guessed it - there’s a back story to how these clothes got to Princeton in the first place. Because Ivy grew in parallel/ response to another casual style movement that was happening around the same time in England.

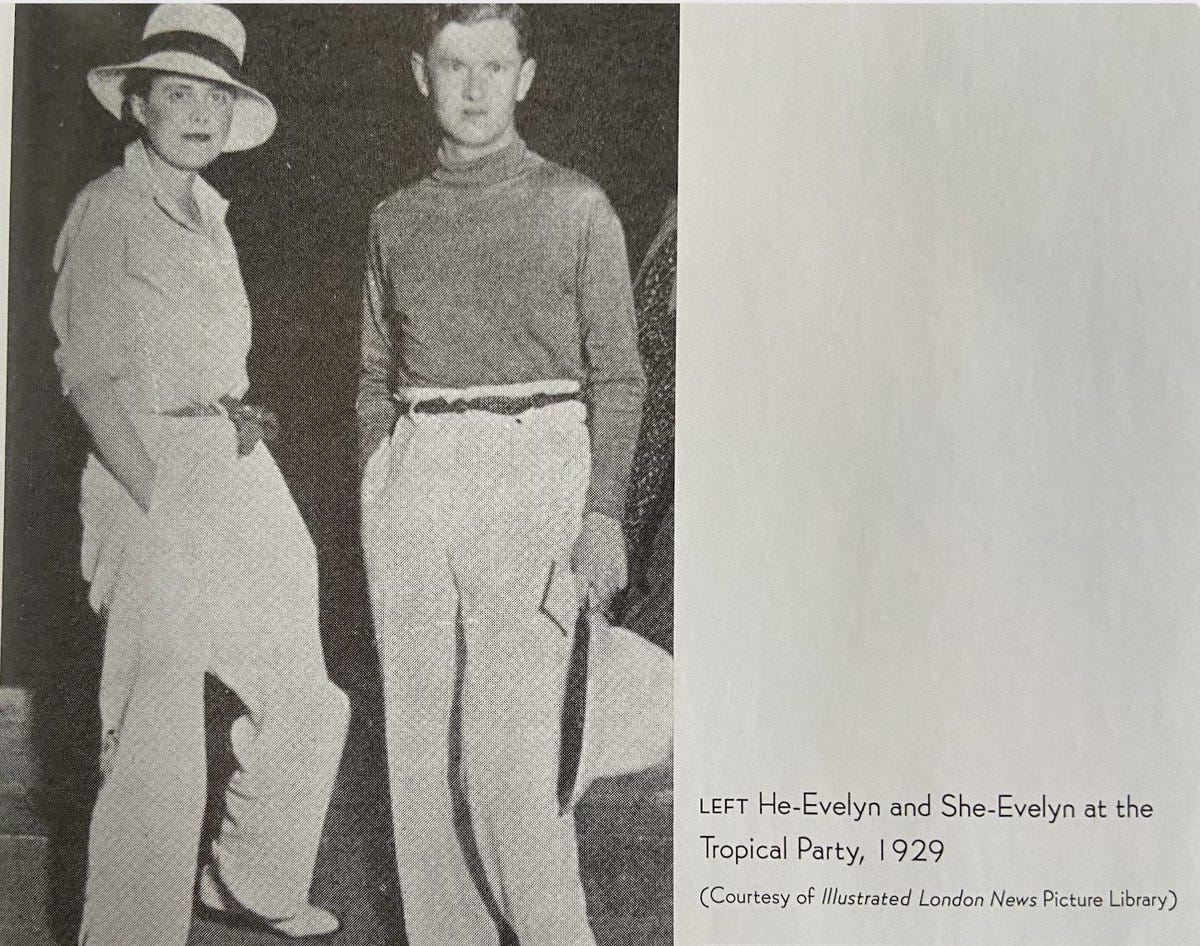

In the 1920s and 30s, there was a new party culture amok in London. They weren’t exactly Ivy per se, but a group of bohemians, known as the Bright Young People (or, eventually, as the movement spread, the Bright Young Things), were constantly running around partying, reveling, and wearing costumes. Their cavalier youthful attitude, seeped into American campus culture. And the English youth, in turn, were very tickled by American campus clothes.

Ok, but this part to me was the twist. It felt obvious that so much of Ivy style would come from England. It’s just such a British-infused look! Even all those sports the Princeton students were playing (tennis, polo) were very English sports. However!

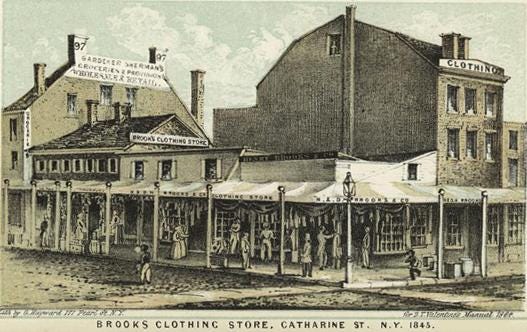

Truly the seeds of Ivy style, if we go back to before the Bright Young People, starts back in the U.S. of A. With the origin story of Brooks Brothers.

So much of the preppy cannon would come from Brooks Brothers. They popularized the oxford cloth button down collar shirt. They softened the polo coat. So much of the Ivy cannon directly comes from this one company…. that just so happens to be the oldest clothing company in the United States. Brooks Brothers is over 200 years old. Check this out- this is the coat that Abraham Lincoln wore to his second inauguration and was also assassinated in. It was made by Brooks Brothers.

The vast majority of American presidents have been clothed by Brooks Brothers. The fun fact the company likes to throw around is that 40 out of 46 American presidents have been clothed by Brooks. The first four presidents couldn’t wear Brooks because they predated the company (which started in 1818)… so since Brooks has been around, only two presidents that haven’t worn it. I’ll tell you who they are later. They’re not who you’d think.

The reason American presidents love to wear Brooks Brothers is extremely tied up with the American democratic experiment. Essentially, after the War of 1812, a bunch of companies, including Brooks Brothers, found a way to make mass-produced, high-quality clothing. This was the birth of ready-to -wear clothes.

At a time when clothing was all made to order, off-the-rack clothes were nothing short of revolutionary. And this newfound clothing accessibility allowed Americans of all classes to look dignified and put-together. And fashion became the embodiment of democracy, and it became symbolically significant that the American presidents wore Brooks Brothers: the mass-produced, simple, modest, ready-to-wear suits of the general populous.

Although Brooks Brothers did not only make simple, modest suits. They made some more ornate ones too. And the logic behind the fancy coats was somewhat counterintuitive.

This coat, also made by Brooks Brothers, was a form of livery- which is to say, dressy servant clothes. And this coat was among the coats that a slave owner purchased for his enslaved property to wear. The fact that Brooks Brothers clothed both presidents and enslaved people- each very differently- is telling.

And this background really adds a layer of meaning by the time we get back to the future, into the 1920 and 1930s, when Brooks Brothers pivoted to making Ivy style clothes, and there was this fashion exchange between the youth of the US and UK… and you start to see an actual member of the British monarchy dress like this:

This is the Prince of Wales, also known as the Duke of Windsor. The one who would eventually abdicate the throne because he was in love with an American, Wallis Simpson. The Prince of Wales also loved to dress like an American.

To put it in snappier terms: the Prince was dressing like a student from Princeton. The heir to the kingdom was wearing mass-produced, simple, modest, ready-to-wear clothes. It was a sign that the American “democratic” form of dressing reigns supreme.

Although Ivy style wouldn’t become truly democratic until it dovetailed with actual policy change. As you’ll learn next chapter, soon all Americans, of all backgrounds, truly would be wearing Ivy style clothes. And it wasn’t because they wanted to look rich, or white, or masculine.

I promise the plot only thickens. This is starting to feel like the Infinite Jest of fashion podcasts.

Yours,

Avery

P.S. Some corrections:

An earlier version version of this story implied that, after War of 1812, Americans had not yet begun kidnapping and enslaving people in the South. This is not true- the slave trade did already exist at this point (and had since, of course, 1619)- it’s just that most raw goods were being sent back to the UK. Most of our fabrics were not domestically manufactured (the mills at Lowell wouldn't start until the 1820s) and so America imported their cotton cloth from England. Thank you to listener Nuria Marquez Martinez for pointing out this ambiguity! I’ve tried to make it clearer!

An earlier version of this story said that Japan was “completely cut off from the rest of the world” for 200 years. This was a very American-centric misunderstanding! As Japanese Historian Eiko Maruko Siniawer so kindly corrected me: “For most of the early modern period, the Tokugawa government was seclusionist toward much of ‘the West.’ But the Dutch were permitted to stay, in Nagasaki and in Edo, and there were Japanese scholars of "Dutch learning" who were exposed to European ideas.” I’ve since softened this language.

My god, you are all so incredible. Thank you for lovingly calling me out on my mistakes!